The Art of being Tomer

High above a highway, in a cluster of tall, grey buildings, Tomer Hanuka and his twin brother, Asaf, are drawing in their bedroom. The windows are open and piles of loose paper on the floor around them flutter in the summer breeze. It’s 1979 and the boys are five. In an adjacent room, Israel’s only television channel babbles away in black and white as they sink deeper into their imaginary world. They don’t know it yet, but this is the embryonic phase of what will be their life’s work. Both boys will grow up to be illustrators equally famous in the comic book arena. But Tomer’s work will spill over into the mainstream and include cover art for books, magazines and albums, not to mention international recognition and a slew of prestigious awards.

After elementary school, the brothers attended an art-based high school where they were routinely disparaged for their efforts. ‘Everybody could draw pretty well in my class,’ says Tomer, ‘but the type of drawing I was into–illustration and comics–was belittled by the faculty. If anything I felt like an underdog.’ When they finally completed high school, Tomer and his brother were then conscripted by the Israeli Army. ‘It’s mandatory when you grow up in Israel,’ says Tomer. ‘I used to feel it slowed me down because I was essentially in a freezer for three years.’ But this period was immeasurably vital in that it made the Hanuka brothers hungry for the future and what it might hold. When their service was up, they went separate ways: Asaf to France where he lived in Paris and studied in Lyon, Tomer to New York, where he worked in a factory in Queens to support himself while attending The School of Visual Arts.

"The type of drawing I was into–illustration and comics–was belittled by the faculty. If anything I felt like an underdog."

Upon graduation, the brothers–still living on different continents–began what would be their first major work: the two-part graphic novel Bipolar. ‘Bipolar lasted five issues,’ says Tomer. ‘Asaf adapted a story by (Israeli author) Etgar Keret, which was later collected under Pizzeria Kamikaze. I wrote and drew short stories, later collected under The Placebo Man. It’s hard for me to look at my work in Bipolar these days; it’s too revealing and inaccessible.’ Revealing or not, Bipolar was an instant cult classic, earning the brothers industry kudos and opening new doors in the world of comic books.

"When that call came it was a relief. It meant that someone was willing to take a risk on a complete unknown for a national magazine."

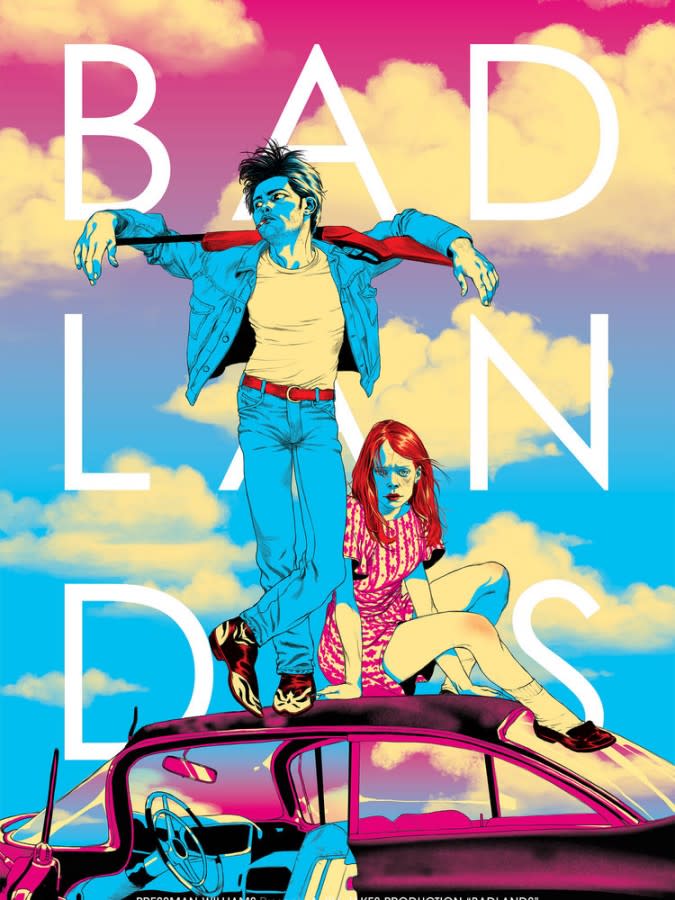

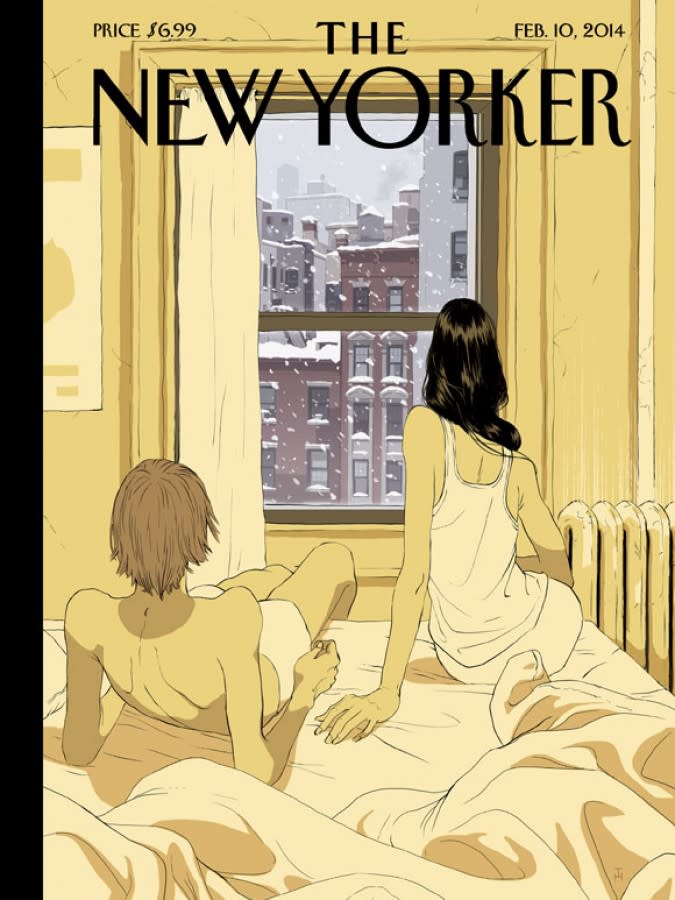

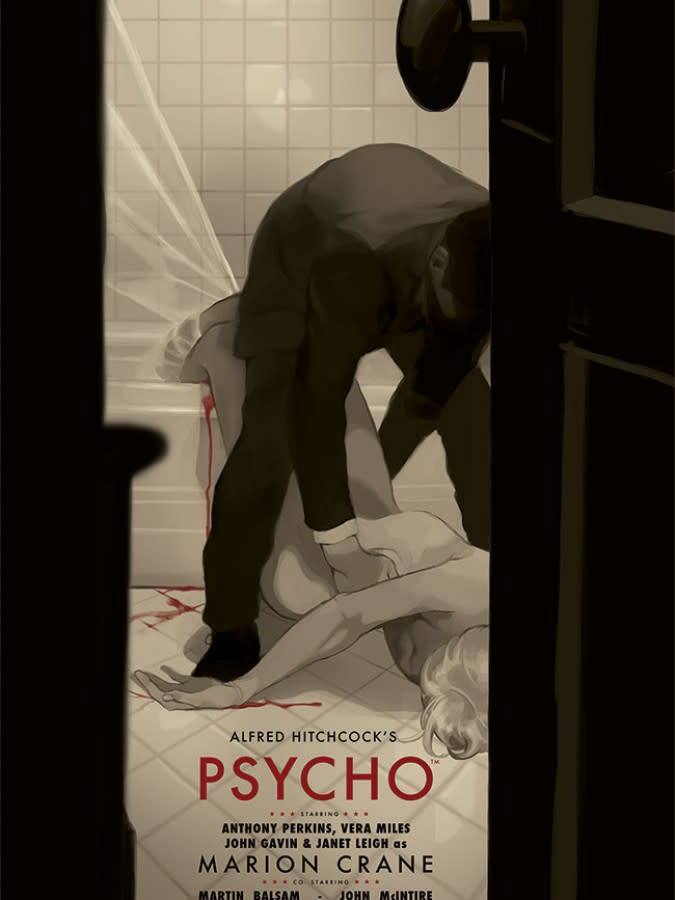

Tomer had also been shopping his portfolio around New York’s major magazine offices at that time, and, a few weeks after graduating from SVA, he landed his first mainstream gig: an illustration in Rolling Stone. ‘It was a portrait of Yusuf Islam, AKA Cat Stevens. I was doing random drop offs with magazines around the city expecting nothing, but when that call came it was a relief. It meant that someone was willing to take a risk on a complete unknown for a national magazine, but even if the whole thing was a huge failure and I’d have to leave the city and get a real job, now I’d be doing so with the knowledge that at least I got my shot.’ It was far from a failure, though, and Tomer’s schedule began filling up with assignments, including book jacket designs for Penguin, Random House, and Scholastic, and commissioned pieces for Playboy, National Geographic, Business Week, Time, The New York Times, and eventually the illustrator’s Holy Grail–the cover of The New Yorker. ‘I came to NYC with The New Yorker in mind as a life goal. I sent numerous ideas for years and years, starting at my freshman year at SVA, and resulting in a hefty collection of rejection letters. When they finally cracked I felt like, “alright, you can get some sleep now.”’

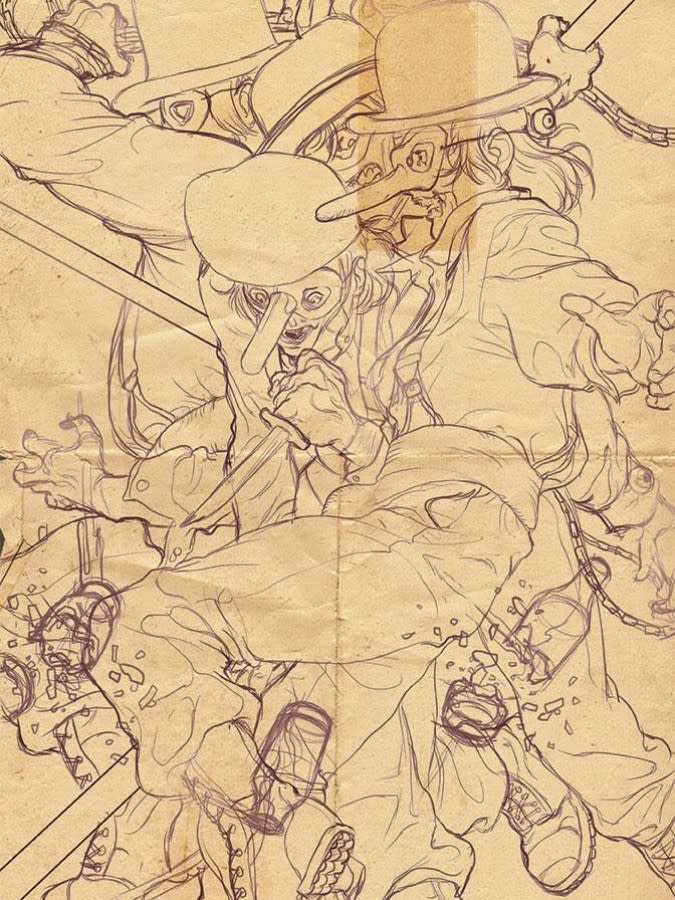

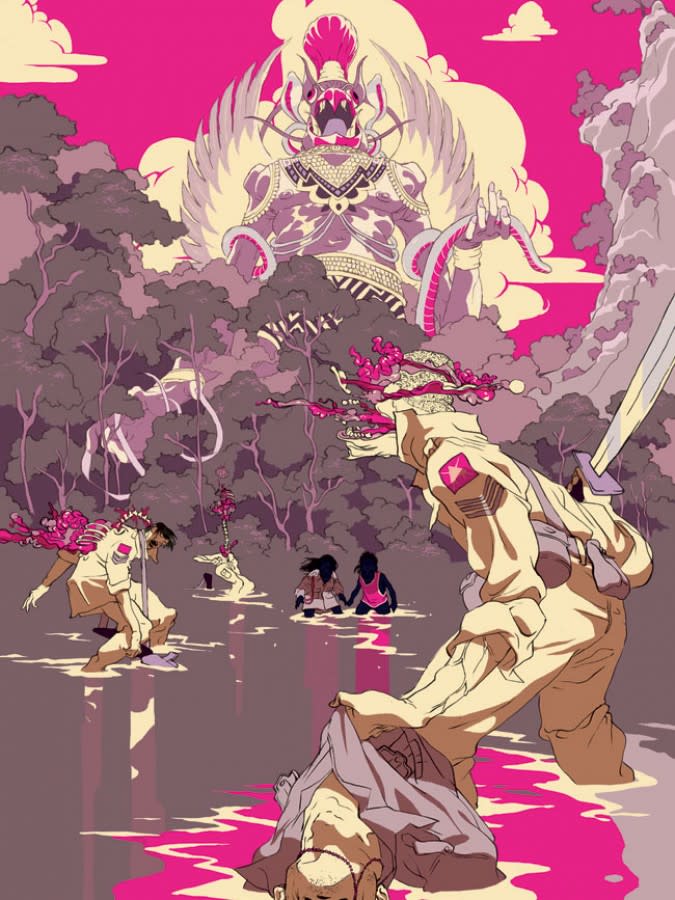

But he didn’t sleep. The work continued (and continues) with a never-ending flow of commercial commissions, a 130-page monograph showcasing his first decade of work (OVERKILL 2011), and deeper involvement with his first love–comic books. His most recent and notable comic co-creation, 2015’s The Divine, is a graphic novel he devised with Asaf and Israeli writer and filmmaker Boaz Lavie. ‘The Divine was pretty straight forward in terms of responsibilities,’ he says. ‘Boaz wrote the story and directed the script with Asaf; Asaf drew the layout and then penciled the pages; I did the inking and the color. I enjoy working over (Asaf’s) layouts because that’s something I can never come up with myself. This type of dialogue that happens in collaborations is maybe the best argument for working with other people. Your own work, which can be frustrating and circular, suddenly feels new.’ The Divine was a certified hit, riding high on the New York Times best-seller list and later winning a 2016 Hugo Award for Best Graphic Story–an award that shares a shelf with Tomer’s other decorations, including two Society of Illustrator Awards, an International Manga Award, a British Design Museum Award, and an Oscar Nomination (as part of the art team on the movie Waltz with Bashir), among others.

Has all the success and adulation changed the way he works? Not really. It’s the same as it ever was: ‘I begin with tiny stamp-size compositions,’ he says. ‘It forces me to focus on the big shapes; I’m looking for something that feels like it has depth in the way the narrative is presented; then I redraw it bigger so I can present it, and by the time I get to the final it has nothing to do with the sketch. The excitement of each stage can only be sustained for one step of the ladder. Which means you've got to reinvent it at every stage or have some sort of discovery about what it’s “really about.” The only way to stop this cycle, though, is a deadline.’

"I’m going to reset the system here. The challenge is to keep the fire burning."

It’s almost forty years now since Tomer and his brother were sketching away on their bedroom floor in Israel, and since then a lot has changed. And there’ll be even more change moving forward, including some ‘serious reorganization’. Tomer doesn’t want to give too much away, but there’s definitely something new and exciting in the pipeline. ‘I’m going to reset the system here,’ he says. ‘The challenge is to keep the fire burning. I have plans.’